September 5, 2025

3 min read

Storm-Tossed Baby Pterosaurs Died with Broken Wings, Fossil Evidence Suggests

About 150 million years ago storm winds snapped bones in the wings of baby pterosaurs, sending them tumbling to their deaths in a muddy lagoon in what is now Germany

An artist’s impression of a tiny Pterodactylus hatchling struggling against a raging tropical storm, inspired by fossil discoveries. Artwork by Rudolf Hima.

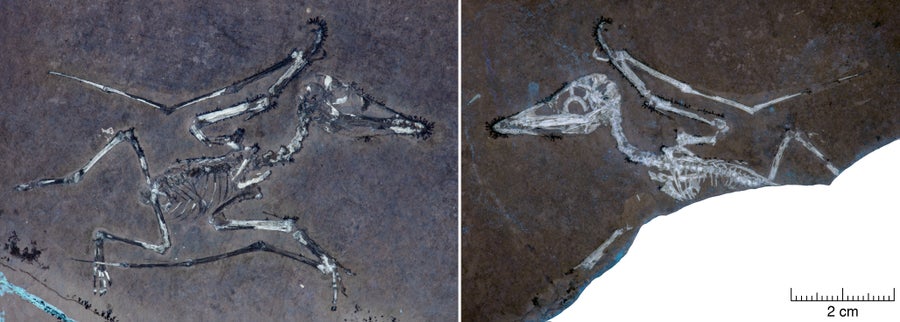

About 150 million years ago powerful storm winds buffeted two young pterosaurs, snapping forelimb bones in their fragile wings and sending them hurtling to their deaths in the muddy depths of a lagoon. Scientists surmised this grisly ending when they newly analyzed the creatures’ fossilized skeletons—displayed for years in two different museums in Germany—revealing these unique traumatic injuries for the first time.

One pterosaur had a fractured right wing bone; the other had a broken left wing. Rather than a clean snap, as from a direct impact, the breaks were seemingly made by twisting forces. Such oblique humerus fractures are known to occur in the wings of young birds and bats when they encounter strong winds during flight but have never before been documented in pterosaurs, the researchers reported on September 5 in Current Biology.

Both pterosaurs were of the species Pterodactylus antiquus and were found in Germany’s Solnhofen Limestone, a site renowned for its fossils from the Jurassic period (201.4 million to 145 million years ago). The wingspans of the two young reptiles measured about 7.9 inches (20 centimeters), and they were no more than a few weeks old when they died.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Because the torquing injuries look like they occurred during flight, the findings add to a growing body of evidence that pterosaurs could fly soon after hatching, says senior study author Dave Unwin, an associate professor of paleobiology at the University of Leicester’s School of Museum Studies in England.

The hatchling Pterodactylus, nicknamed Lucky, illuminated UV light. Both part and counterpart show the delicate bones of this tiny pterosaur, capturing a fractured wing in extraordinary detail.

‘A Medusa Effect’

Unwin and lead study author Robert S. H. Smyth, at the time also a paleontologist at the University of Leicester, examined the fossils under ultraviolet light, which made them fluoresce and revealed breakage details that had been previously overlooked. In Germany, one specimen had been housed at Museum Bergér, and the other was in the collection of the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum. Smyth and Unwin gave the specimens ironic nicknames: Lucky I and Lucky II.

Along the fracture lines, bone tissue showed “pronounced displacement,” which is typically seen in twisting injuries, the researchers reported. The bones were flexible when they snapped, and there was no sign of healing. This told the scientists that the injuries happened when the pterosaurs were alive but that they died soon after.

Pterosaurs had fragile bones, and their fossils are quite rare. Preserving specimens as complete as these “requires an ideal set of conditions,” such as those found in the Solnhofen Limestone, says Victor Beccari, a doctoral candidate researching pterosaurs at the Bavarian State Collection for Palaeontology and Geology in Germany. “Finding these juvenile pterosaurs with direct evidence of trauma in such a high degree of preservation highlights the uniqueness of the Solnhofen fossils,” says Beccari, who wasn’t involved in the new study. The two pterosaurs bring new evidence about flight at a very young age, “with an added snapshot of the dynamic paleoenvironment they lived in.”

The findings also suggest a sinister new interpretation for the hundreds of pterosaur fossils, mostly of very small and very young individuals, that have been found at Solnhofen. It wasn’t a habitat where small pterosaurs flocked and thrived—it was a death trap for hatchlings. Their tiny bodies were battered and broken by winds and then buried in anoxic mud at the lagoon bottom, which preserved their remains as fossils, “almost like a Medusa effect,” Unwin says.

At other sites, adult pterosaur fossils are more common, Unwin says. Mineral deposits in Solnhofen suggest that during the Jurassic, the region was frequently visited by storms that stirred up lagoon sediments and lashed the area with powerful wind gusts. Adult pterosaurs could probably avoid the storms, “which is why we don’t see large, complete, beautifully preserved adult pterosaur skeletons in the Solnhofen Limestone,” he adds.

Though Solnhofen was one of the first sites to reveal abundant pterosaur fossils, paleontologists are now realizing that its snapshot of the Jurassic is highly specific to certain conditions in that location, creating a biased fossil record. But that also presents new opportunities to interpret how pterosaurs lived—and how they died.

“It’s a step forward,” Unwin says. “The better we understand how things get preserved, the better chance we have of reconstructing true pictures of what life was like in the past.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.